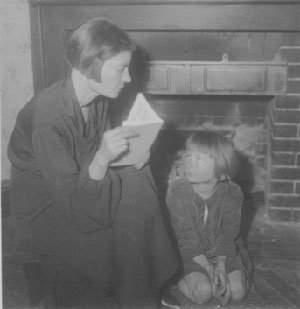

Dorothy Day with her daughter, circa 1932. From the Dorothy Day-Catholic Worker Collection at Marquette University .

Dorothy Day (1897-1980), along with Peter Maurin, founded the Catholic Worker movement in 1933. As Laurence Downes recently summarized the tenets of this enduring human experiment in the New York Times:

Before converting to Catholicism, Dorothy was a journalist and something of a leftist, campaigning against U.S. participation in the great "capitalist war," (World War I) and for women's votes. Her subsequent writings in books and the Catholic Worker newspaper had as a primary aim, always, to share the delight and freedom she found in her encounter with the Christ; what made her such an engaging writer and thinker was that her evangelism was always embodied in vivid descriptions of mundane practicalities.Members still dedicate themselves to voluntary poverty, nonviolence and hard work. They make soup, give away coats, visit prisoners and the sick, protest against war and publish a newspaper that sells, as it did in the 1930's, for a penny.

Dorothy was also the only person I knew well who lived through the 1906 earthquake, in her case as an eight year old in Oakland. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the quake, it seems right to share her story. This autobiographical account appears in The Long Loneliness, still in print and available.

Dorothy's account of the terror of that shaker does unsettle my complacent expectation that the earth will always sit solidly, doing its job of holding the city upright. One day it may not, but there is no knowing when. I find I can't hold the thought. I'm glad I don't have a professional responsibility for trying to get people to prepare for the unimaginable.We did not search for God when we were children. We took Him for granted....

[As a young child,] as soon as I closed my eyes at night the blackness of death surrounded me, I believed and yet was afraid of nothingness. What would it be like to sink into that immensity? If I fell asleep God became in my ears a great noise that became louder and louder, and approached nearer and nearer to me until I woke up sweating with fear and shrieking for my mother. ...

Even as I write this, I am wondering if I had these nightmares before the San Francisco earthquake or afterward. The very remembrance of the noise which kept getting louder and louder, and the keen fear of death, makes me think now that it might have been due to the earthquake. And yet we left Oakland almost at once afterward, since my father's newspaper job was gone when the plant went up in flames...I remember these dreams only in connection with California....

Another thing I remember about California was the joy of doing good, of sharing whatever we had with others after the earthquake, an event that threw us out of our complacent happiness into a world of catastrophe.

It happened early in the morning and it lasted two minutes and twenty seconds, as I heard everyone say afterward. My father was a sports editor of one of the San Francisco papers. There was a racetrack near our bungalow and stables where my father kept a horse. He said that the night before had been a sultry one and the horses were restless, neighing and stamping in their stalls, becoming increasingly nervous and panicky.

The earthquake started with a deep rumbling and the convulsions of the earth started afterward, so that the earth became a sea that rocked our house in a most tumultuous manner. There was a large windmill and water tank in back of the house and I can remember the splashing of the water from the tank on the top of the roof.

My father took my brothers from their beds and rushed to the front door, where my mother stood with my sister, whom she had snatched from beside me. I was left in a big brass bed, which rolled back and forth on a polished floor. ...

When the earth settled, the house was a shambles, dishes broken all over the floor, books out of their bookcases, chandeliers down, chimneys fallen, the house cracked from the roof to ground. But there was no fire in Oakland. The flames and cloudbank of smoke could be seen across the bay and all the next day the refugees poured over by ferry and boat. Idora Park and the racetrack made camping grounds for them. All the neighbors joined my mother in serving the homeless. Every stitch of available clothes was given away.

All the day following the disaster there were more tremblings of the earth and there was fear in the air. ...As soon as possible we pulled out for the East.

No comments:

Post a Comment